Through-hulls

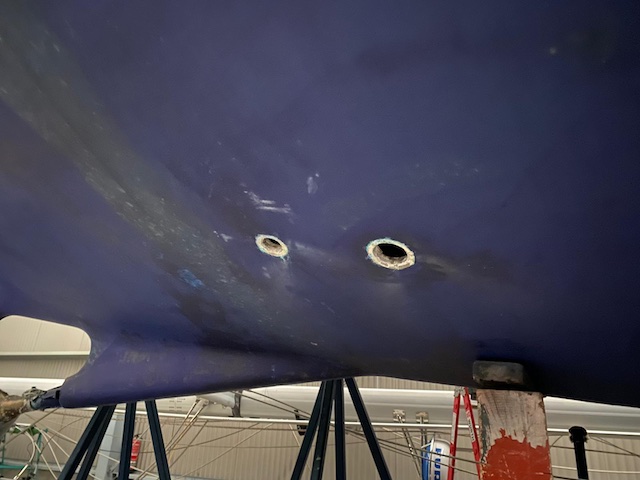

Two through-hulls of the same age from the same boat. One is made of bronze (right) the other one of brass (right). Compare the thicknesses of the remaining metal!

Boats are getting older and equipment and fittings have to be serviced, inspected and changed. While some materials seem to have an eternal life, others definitely don’t! The lead in the keel never has to be exchanged, some other parts of the boat do need the same attention. Many have their rigging checked and changed ever 10-15 years, but not all are checking their through-hulls with the necessary attention.

Vintage boats are increasing in number and care must be taken in order to upkeep the safety of older boats. Old boats are per se not less safe as long as they are looked after.

Below is a post in Instagram from Michael and Claudia, who just bought their Moody 33CC for their bluewater plans. They posted some photos and wrote:

bigfootsailsaway

Our boat almost SANK?

”We bought our Moody in Belgium last fall and had to sail it to the Netherlands. We did not have the chance to get any work done since the boat was hours away, so we had to take the risk and sail it up North.

Luckily, all went well and we arrived in our harbour, where we were hauled out the next day. One of the first things we had to get done was replacing all through hull fittings that were below the waterline.

To our shock: Michael was trying to remove the hoses and one of the seacocks just BROKE OFF. Things could have gone really wrong. Not sure how fast a boat can sink with a hole that size?

We are feeling so much safer now that we replaced them all.”

In the olden days, through-hulls were solely made out of bronze. It was good seamanship to only use an alloy that doesn’t contain any zinc. Zinc, being less nobel than other metals, is often used to be sacrificed in order to safeguard other metal. Anodes are made out of zinc, for instance, and need to be replaced regularly since they are scarified and “eaten way” by galvanic corrosion. If through-hulls and valves are made out of an alloy containing zink, we have a problem, since over time, the zink will be scarified and “eaten up” as well.

Brass

Modern production boats often use brass, albeit something they call “marine brass”. This contains less zinc than in (yet) cheaper brass, but still it does contain zinc!

There are many types of “marine brass” but they all have the zinc in common, sometimes up to 40%:

- “Red brass” or “DZR-brass” (De-Zincification Resistant): 85% copper, 15% zinc

- “Cartridge brass”: 70% copper, 30% zinc

- “Muntz metal”: 60% copper, 40% zinc

- “Admiralty brass”, 70 copper, 30% zinc;

- “Naval brass”: 60% copper, 40% zinc

- “Aluminum brass”: 76% copper, 22% zinc, 2% aluminum

- “Manganese bronze”: 60% copper, 40% zinc.

Note: “Manganese bronze” is bronze in name only; because of its zinc content, it resides squarely in the brass family.

The above are said to be salt-water resistant, but only as long as we have absolutely no galvanic corrosion involved! The conditions that trigger galvanic corrosion are:

- An electrolyte bridging the two metals, which may not necessarily be aggressive to

the individual metals when they are not coupled; - Electrical connection (direct contact) between the metals;

- A significant difference in potential between the two metals to provide a significant galvanic current;

- A sustained cathodic reaction on the more noble of the two metals, in most practical situations the consumption of dissolved oxygen in the electrolyte.

It’s worth repeating: All the above mentioned brass types do consist of zinc, no matter their name or your sales person’s convincing assuring! According to my own opinion, brass is simply ill-suited for any application where it’s called upon to convey, direct, or stem the flow of seawater, regardless of whether it’s used above or below the waterline. Full stop!

Bronze (left) and brass (right) from the same boat.

Bronze

The traditional alternative is obviously bronze which has been used in boatbuilding for the last 100 years, however not always during the last 30 years or so. Bronze, although it’s a copper alloy, is different from brass in that it’s free of any appreciable amount of zinc, and so is not susceptible to dezincification. Bronze’s parent alloying element is copper, but its primary alloying element is tin. As a result, pound for pound, bronze is often more expensive than brass, which contains less costly zinc.

On the above photo, you can clearly see how the brass has been eaten away, while bronze is still as strong and thick as before. both through-hulls have been sitting side-by-side on one of the same boat, but the bronze fitting was a direct supply by Volvo-Penta which was included in the “engine package” to be installed by the yard. The brass through-hull next to it, was the choice of the yard, who obviously wants to save money, since bronze is more expensive than brass. 15 years on, the brass through-hull had become very weak.

And just so you don’t think it’s a one-off: Many boats suffer from the same fate and are still afloat more thanks to luck and the lack of anyone kicking the valves.

Here is another recent example, this time from a 20 years old boat from a renown brand. Also this through-hull was so thin that it could be cut through with a knife! See video at the bottom of this page.

Why take the risk?

The big problem is that not all installations suffer! Some through-hulls and valves can last much longer than others – even if they are installed side by side on the same boat. One is eaten away, while the other one is still looking thick with a lot of material left. And you can’t tell from the outside!

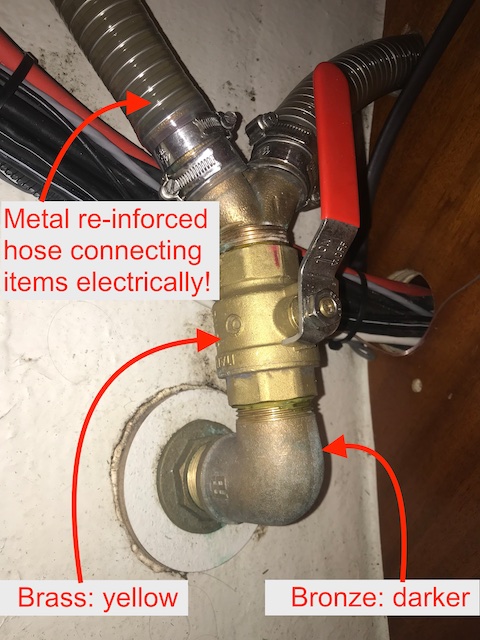

There are many reasons why this can be so different, e.g. what type of hoses you have used (conductive hoses containing carbon or metal-reinforced leading electrical current?) or what type of liquid is inside the valves and through-hulls (e.g. salt water or acid rain from the deck drains?). The most important factor is if the boat has been using shore-power without an isolation transformer installed. An isolation transformer helps eliminating galvanic corrosion as a result from faulty electric installations onshore or from neighbouring boats.

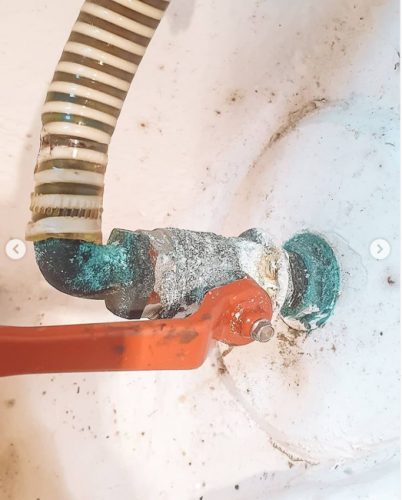

This is how my through-hulls looked like when I bought Regina Laska in 2012. I am sure I could have kicked the entire tower with my foot…!

What is really bad is, if you don’t know what alloys you have and you mix and match!

Very unlucky marriage: Brass replacement valve screwed onto a bronze skin fitting. Galvanic corrosion is on order! This solution will not hold more than a couple of seasons before the brass is scarified for the bronze. In addition: Metal-reinforced hose leading direct current (DC) between connected items giving galvanic corrosion. Also salt-water inside the hose is conductive as well!

And even if there are installations that work for decades despite using brass, why take the risk?

In order to sleep well, you should at some point in time consider changing your through-hulls if they are made out of any type of brass, no matter how they look from the outside. I would personally consider changing brass through-hulls when they get over 10 years old.

So, what should I use instead?

The traditional answer is bronze. I did right that when I did my first and major refit in 2012-13. Initially, I was happy with my bronze through-hulls, but they had some other issues, being the fact that their handles corroded and the ball valve inside got very hard to more und some of them even got stuck, seized and others broke inside so the handle moved in “idle”.

What I didn’t know is that the inside my strong-acting bronze seacocks, in other words the ball and the mechanics moving it, often consists of much weaker material! Dunken Kent puts it so well in his article in a recent issue of SAIL MAGAZINE, when he says: “While they might have DZR (De-Zincification Resistant) bodies, they frequently have brass or stainless-steel ball valves and mild steel handles. The former can seize up if not turned on and off regularly. The latter will simply rust away and possibly snap off in as little as a matter of months.”

My through-hulls including skin-fittings and ball valves are today made out of bronze. You can see the dark colour. If you are not certain what you have, take a knife and scratch on the surface. Underneath you will see the true colour. If it’s bright yellow, it’s brass! By the way: Note the orange fire-proof covers on all hoses in the engine room which are under the water line. This is important, since, in case of fire, the hoses would otherwise melt and water would penetrate and potentially sink the boat before one gets into the burning engine room to close the valves!

Don’t take me wrong! The outer body is bronze and very durable! But while often just the outer bodies of the valves are made out of bronze and the entire skin-fittings are made of of bronze throughout, it’s the interior of the valves that give problems: the ball valves of many bronze valves have had a life-span of not much more than cheap brass valves, despite the outer skin being bronze. I already exchanged all mild steel handles with custom-made stainless steel handles two years ago but no less than 3 ball valves had to be changed already. Very disappointing!

Below a photo from one of my 8 year old through-hulls when they were taken out in 2021. As you can see, their material is still thick so the skin fitting and their outer body is still going strong. It’s just the inside of the valve itself, that they get more and more difficult to move (despite moving them every few weeks) and in the end, the inner parts corrode.

One of my disassembled through-hulls in 2021. After 8 years the bronze is still thick as new. It’s just the ball that gets stuck inside the valve that is the problem: Despite the superior bronze material, the inside isn’t any better than the cheaper valve types, unfortunately.

Composite – but go for the best!

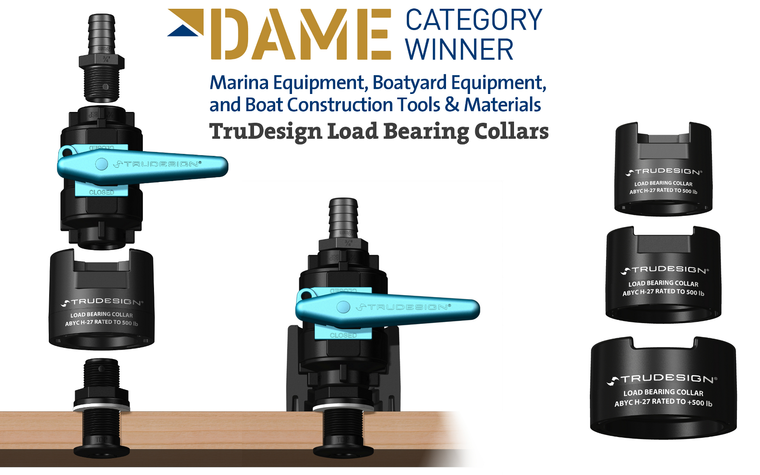

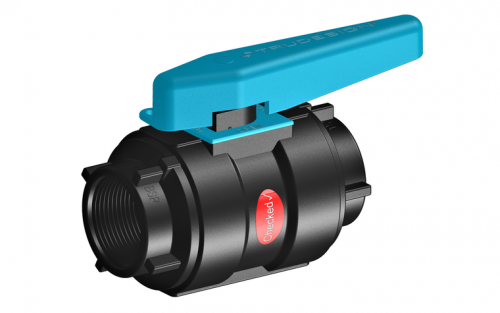

After 8 years with bronze, I am now totally going for composite material. Not all brands are good and there are many cheaper copies, so, obviously, I went for the one I trust the most: TruDesign from New Zealand.

These are said to last for at least 30 years and are certified by 5 bodies, including Bureau Veritas for commercial use and fulfil the stringent rules for fire safety. They have won a lot of awards, including the 2016 & 2015 DAME Award Winners, 2016 HISWA ‘Product of the Year’ nominee, & 2009 HISWA Innovation Award Winner. It doesn’t hurt that they have been around for 40 years either, and the fact that they are made out of non-conductive material also leaves behind the question if you should bond or not to bond your through-hulls against galvanic corrosion and you don’t have to ponder over hoses that might give any galvanic corrosion.

Time will tell if I can become one of the many sailors testifying about their superiority and ease of handling. The number of high-end boatbuilders using TruDesign and many serious boat owners testify that this is the way forward.

At least, that’s what I believe today.